Air pollution→dementia: Friday thoughts

Plus: Brook Shields on "tending" | chronic diseases vs. chronic conditions | No wonder our childhoods felt so different and less crowded

I failed to publish this post yesterday because I just ran out of time before Substack became a Friday-afternoon ghost town. Mea culpa.

Here’s the latest notable news and ideas in aging with strength:

But first, in case you missed it….

1 | Air pollution now strongly linked to higher dementia risk

A sobering new research paper in The Lancet drew significantly stronger associations than previous studies had between long-term exposure to air pollution and dementia. By examining dozens of previous studies comprising almost 30 million people over the course of more than 20 years, this rigorous meta-analysis found breathing three key pollutants significantly increases dementia risk:

PM2.5 (ie, fine particulate matter 30x smaller than the width of a single strand of human hair) created an 8% increased dementia risk per 5 μg/m³ increase in exposure.

PLAIN ENGLISH TRANSLATION: A 5 μg/m³ increase in PM2.5 means there are 5 additional micrograms (each microgram is one millionth of a gram) of tiny particles smaller than 2.5 microns (each micron is one millionth of a meter) suspended in every cubic meter of air you breathe.

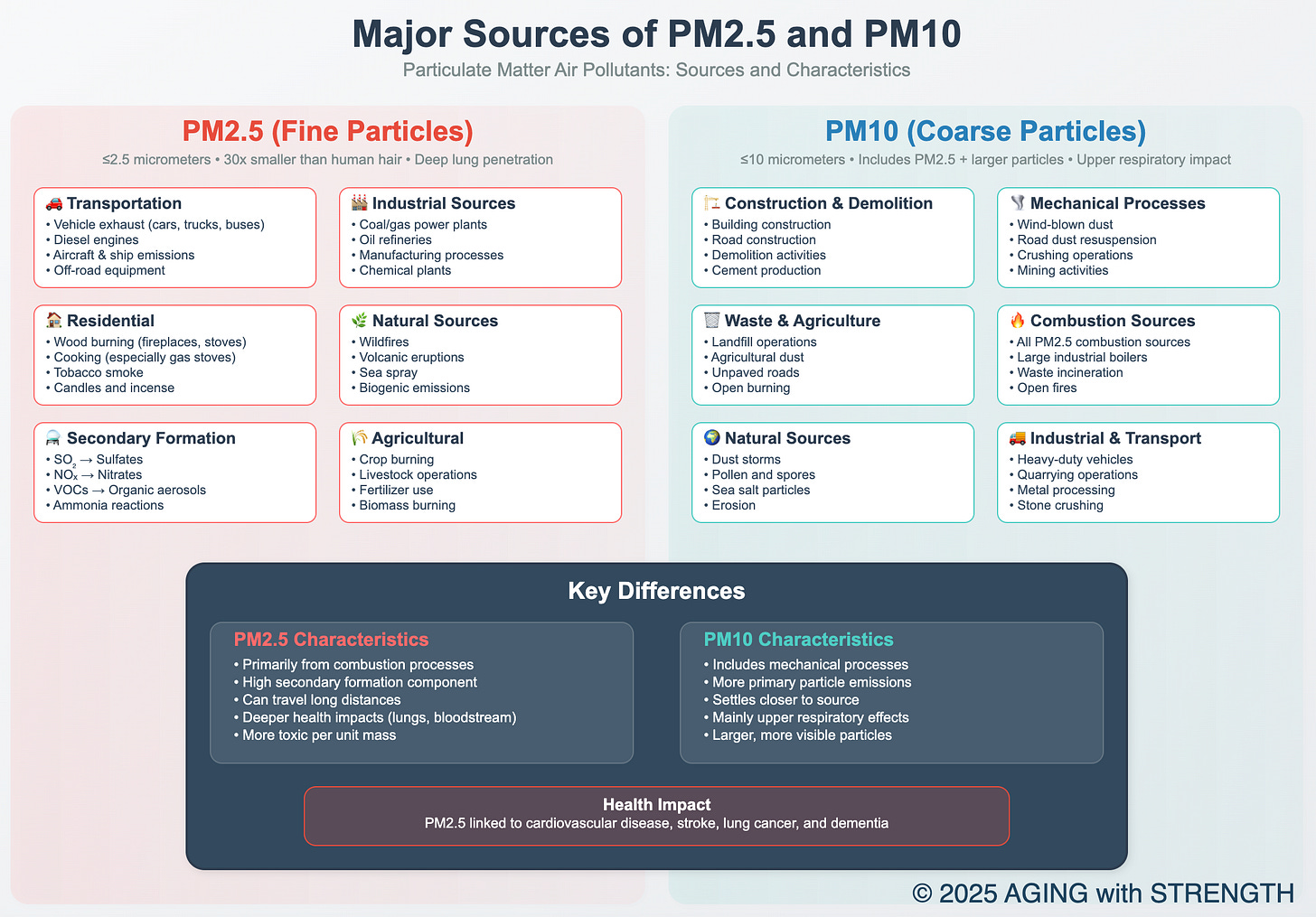

see the chart below to understand where PM2.5 and larger particulate matter called PM10 (because they’re at least 10 microns in size) come from.

NO2 (nitrogen dioxide): 3% increased risk per 10 μg/m³ increase

Black carbon/PM2.5 absorbance: 13% increased risk per 1 μg/m³ increase

The study found no significant associations for nitrogen oxides (NOx), PM10 or annual ozone exposure, though these analyses were based on fewer studies.

The PM2.5 increased dementia risk in context

An 8% increased dementia risk per 5 μg/m³ means that relatively modest increases in air pollution — roughly equal to the increase you would experience by moving from a clean suburb to a city center, or from moving from Vancouver, Stockholm or Helsinki to Houston, Madrid or Singapore — carries measurable long-term cognitive health consequences.

What makes this paper’s findings particularly concerning is the indication that even moderate levels of air pollution that are well below what millions of people now routinely breathe in major cities worldwide, can significantly impact brain health over time.

Remember those science fiction movies where people in a dystopian future go to “oxygen bars” to mask up and breathe freely? Given the current trajectory of Earth’s worsening air quality, some scientists are already warning of a coming “dementia pandemic.”

2 | Is a “chronic disease” the same as a “chronic condition”?

Turns out, science doesn’t have a single answer to that question. That lack of precision matters because of how scientific health research often uses these terms interchangeably when reporting the ever increasing prevalence of long-term disease in, say, American or European societies.

In a Q&A interview of Dr. Eric Topol, the author of “Super Agers,” published by WBUR in Boston, the reporter uses “chronic disease” and “chronic condition” almost interchangeably to refer to “cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular issues” that prevent people 80 and older from achieving what Dr. Topol categorizes as super agers.

…or make a one-time contribution. It really does make a difference!

Curious, I looked up the definition of each phrase. Turns out, even scientists can’t agree on what each term means, exactly. For instance, a CDC trends report published in April 2025 concluded that “8 in 10 midlife, and 9 in 10 older US adults report 1 or more chronic conditions” (italics mine). The report defined the term in detail:

“Having a chronic condition was defined as responding yes to having ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that the respondent had any of the following: arthritis; cancer, excluding skin cancer (cancer); COPD; depressive disorder (depression); diabetes (excluding during pregnancy only); heart attack, angina, or coronary heart disease (heart disease); high blood pressure; high cholesterol; CKD; or stroke. Additionally, current asthma and obesity (body mass index ≥30.0, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared from self-reported weight and height) were included as chronic conditions.”

(Note the passive-voice verb in the final phrase above — “were included” — indicating it was a choice made by a person who could have made different choices.)

Not exactly iron-clad science, but okay. I appreciated the specificity, even if it meant that I, myself, wouldn’t become a super ager because my congenitally high cholesterol technically counts as a “chronic disease.”

Or is it actually a “chronic condition”? And if it is, should I care? Turns out, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), a premier global research organization, asked pretty much the same question in 2016, in a paper titled, “Use Your Words Carefully: What Is a Chronic Disease?”

The paper notes how the CDC, at least in 2016, defined the term with one set of conditions while another U.S. federal agency, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, used a broader definition that included more diseases. The WHO uses a third definition.

The 2016 NIH paper noted:

”Differences in how ‘chronic disease’ is used are largely dependent on the data used for the research and the discipline of the lead authors.” And later: “Popular Internet sources used by the general public to gather medical information use the terms ‘chronic disease’ or ‘chronic condition’ to mean slightly different things.”

Fun Friday experiment: The next time you talk with your doctor, ask her what the difference is between these terms.

3 | Brook Shields on the importance of “tending”

A couple weeks ago, The Healthy, a Reader’s Digest publication, published a profile of Brook Shields, 59. In it, there’s a link to a previous 2023 interview with Shields in which she discusses “what nature has taught her ‘about cycles, and the importance of water, and time spent tending.’”

The article didn’t follow up on her tending comment, but it reminded me of another idea — “mattering” — that I wrote about in a recent post. They’re different ideas, but they fall into that same intellectual/emotional in-between place in our minds and hearts: things we should be doing more often that, when we become aware of them, we instantly understand as healthy and good for us and those around us.

In this case, I immediately thought of tending the plants in my house, which I only recently bought because green living things are good to have around. I love tending plants! Not least because it gives me time to think and rethink thoughts that need time to marinate, percolate and settle.

4 | Why the world felt so much less crowded in 1970

Because it was. The United Staes in 1970 contained just over 200 million people, compared to 340 million today — 40 percent fewer humans. There were fewer people driving fewer cars going to fewer places located farther apart, by an order of magnitude, compared to what children and the rest of us experience today.

Check out this animated graphic of U.S. population growth, by state, from 1790 to 2020 (scroll down the page a bit, to see the moving graphic). You can watch different parts of the graphic 20 times and learn something new each time. For example, I didn’t realize that:

In 1900, more people still lived in Mississippi than in California.

In 1940, California was still only the fifth-largest state by population, behind NY, PA, IL and OH (barely). By 1950, California had become the second-largest state by population but still with 30 percent fewer people than New York.

Right up until my birth year, 1966, New York State had more people than California, and Illinois was more populous than Texas.

Human communication during our childhoods consisted of either face-to-face conversation, three network television channels, radios, wall-mounted telephones and envelopes & stamps. And that’s all, folks.

It’s no wonder that, culturally and politically, the United States in our early childhoods felt like a much different, less crowded and less anxious country from the constantly buzzing, belching and always-angry mega-machine it is currently.

More fun facts: In the 10 years between 2010 and 2020, the number of older people in the United States grew at the fastest rate since 1880 to 1890. In 2020, about 1 in 6 people in the U.S. were 65 and over. In 1920, that ratio was less than 1 in 20. (source)

Thanks for reading.

Love how you pulled this research together.

It’s astonishing to think we take in ~11,000 liters of air a day—so even “moderate” PM2.5 exposure adds up.

The ultra-fine particles are small enough to cross the blood–brain barrier and settle in brain tissue (both via blood stream and olfactory pathway), which makes indoor air quality just as important as outdoor.

For me, a purifier with both HEPA and activated carbon (to catch VOCs from furniture, paint, also chemicals of exterior origin etc.) is a must-have, and I have several of these at home!

You forgot!