Q&A: America's deathfood crisis & its cures

A DePaul professor argues that only technology will save Americans from diseases caused by cheap, ultra-processed foods. Is he right?

If you find this reporting helpful, consider becoming an AGING with STRENGTH supporter or making a one-time donation. Your support matters.

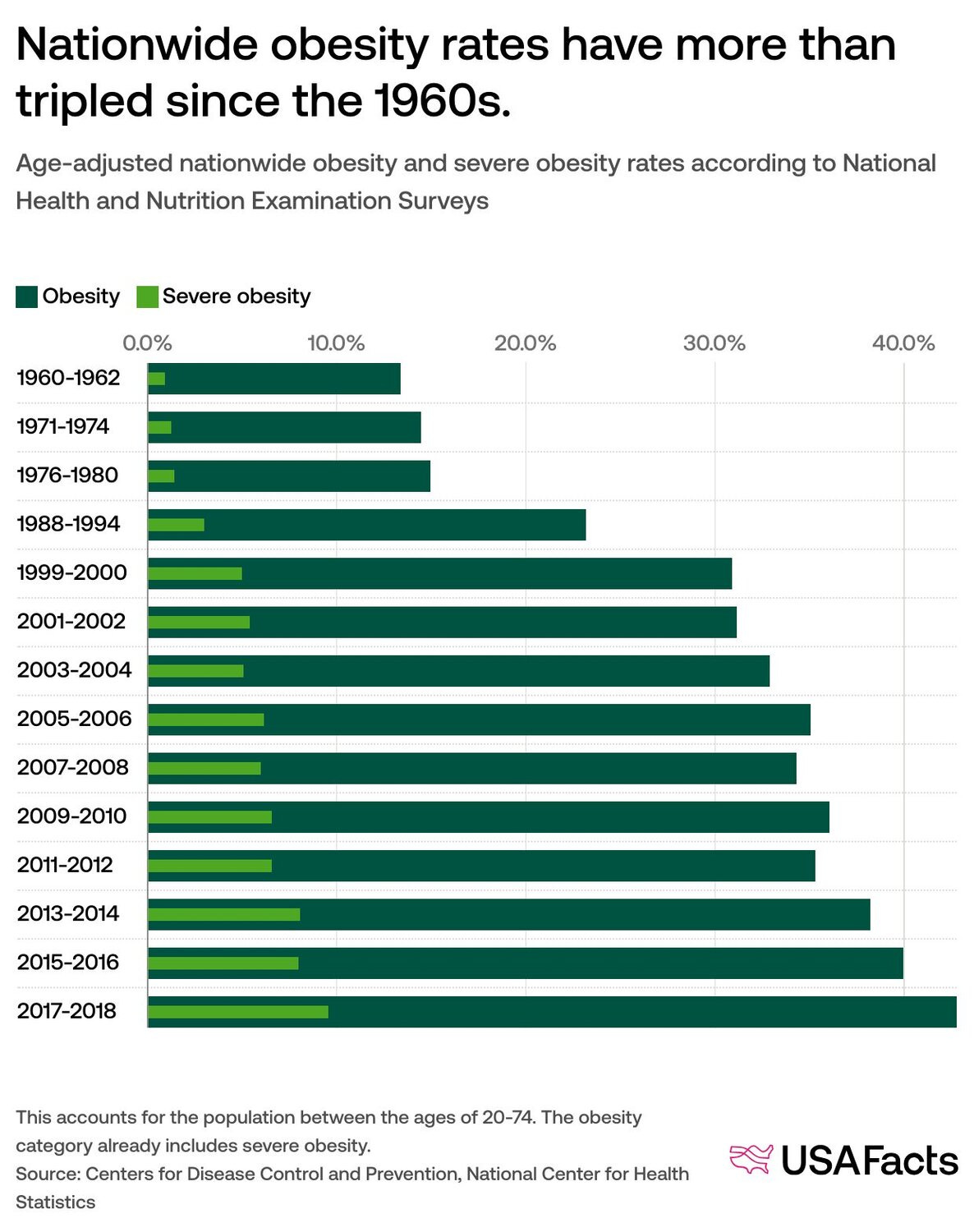

Last week, The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed1 titled, "Prosperity Made Us Fat, and Biotech Will Make Us Thin.” It argued that America’s chronic disease crisis is an unavoidable result of “a civilizational triumph”: ubiquitously cheap, delicious and “energy-dense” (aka ultra-processed) food.

The essay’s author is Anthony Lo Sasso2, a professor of economics at DePaul University, whom I interview in the Q&A below.

In his op-ed, Lo Sasso argues that the epidemic of diseases unleashed by our addictions to soft drinks, packaged snacks, cereals, processed meats, fast food, and prepackaged frozen meals — problems he calls “side effects” of prosperity — can be solved only by emerging technology-driven drugs like GLP-1s and their ilk.

“This is what scalable change looks like in a rich society,” Lo Sasso writes. “We use science to keep the gains of prosperity while softening the unintended consequences.” You can read a non-paywalled version of the full essay here.

What about individual agency and Big Food’s lies?

These were among the questions I put to Lo Sasso, who graciously accepted my invitation to dispute his op-ed’s thesis via a 40-minute phone conversation.

I’m sharing that dialogue with you here because my view is that there are many culprits in America’s unmitigated addiction to industrialized deathfood3, among them not just consumers’ poor choices but also food producers’ profit-driven intent to keep their customers ignorant and in the dark4.

In his op-ed, Lo Sasso dismisses efforts to educate consumers about nutrition as “label skirmishes.” We get into that and much more below. Including my questions

about the importance of individual agency. We each have a responsibility, I believe, to understand the consequences of eating our way into cardiovascular disease, certain cancers and metabolic dysfunction, each of which are strongly associated with Americans' high consumption of ultra-processed foods.

And I’m not alone in that belief.

To my mind, Lo Sasso’s op-ed ignores how the food industry has deliberately shaped the national food environment to make healthy choices difficult and more expensive — through lobbying against regulations, targeting children with marketing and deliberately engineering foods to fool our brains’ satiety signals.

We had a good, and good-faith, discussion. I’m eager to hear what you think of it.

Q&A: Anthony Lo Sasso, DePaul University economics professor

(This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Paul from AGING with STRENGTH: Professor, I appreciate your willingness to take time from your schedule to talk with me. I disagree with a lot of what I read in your Wall Street Journal op-ed, in which you argue that food today is abundant, delicious and calorie-dense, and that the obesity epidemic that cheap food has unleashed can be solved only with technology.

Anthony Lo Sasso: We live in an historically unprecedented time where food is plentiful and there is in this country virtually no threat of starvation. That’s astounding and amazing and wonderful. At the same time, we’re also benefiting from the lack of need to devote our time to backbreaking work. These kind of Titanic shifts in civilization are not going to be easily undone. Yes, there are downsides. If we want to preserve all that we have, which I can't stress enough how wonderful and amazing this is, it's going to require continued innovation and scientific advancement. I point to some of these nascent trends in biotech in the form of GLP-1s.

AGING with STRENGTH: Aren’t you giving the food industry a huge pass? Food today may be nutrient dense and cheap, but it's also causing the chronic diseases you rightly call a crisis.

Lo Sasso: What I'm talking about is much, much larger and civilizational in scope. It's much bigger than “the food industry,” because food industry is just the label we attach to this abundance that we enjoy. We are, literally, in a world where you could buy a box of pasta for, what, a dollar? And that would give you a day's worth of calories. Is that the optimal mix of nutrients? Is it the best food that your body needs to optimally sustain itself? No, certainly not. But could you survive? Heck yeah. In the grandest sweep of human history, that is truly extraordinary.

AGING with STRENGTH: Where is the personal agency part of this equation? Isn't what you dismiss as "label skirmishes" (agitating for greater nutritional clarity on food labels) a diminution of a huge problem; namely, that many people don’t know what they don’t know about the negative impact of their diets?

Lo Sasso: Agency is costly. And it’s difficult to change one's behavior. When I say costly, I mean it in the way an economist means it. Resisting those urges are psychically costly to us. The urge is to overindulge, when it's cheap and plentiful and easy to get and delicious. Denying that exerts a psychic cost on each and every one of us. I am a runner and cyclist. I work out every day of the week, usually multiple times a day. I have been tracking my calories for about the last decade plus. So I know what I'm talking about when I say about the cost. It is bloody hard.

AGING with STRENGTH: What about public health programs that have proven extremely effective, including those targeting smoking? If we applied your argument about cheap food to tobacco use, you’d essentially be conceding that smokers are going to smoke, they’re not going to stop on their own, so let’s invest in tech-driven drugs to mitigate all the cancers they’ll get from cigarettes.

Lo Sasso: I worked in a school of public health for 15 years. I'm familiar with the role of public-health education campaigns. I’m also very cognizant of their limits. We have probably known for a very long time, but at least since the Sixties, when the first surgeon general report was issued on cigarette smoking being a possible cause of lung cancer. And yet, today, roughly 15 to 20 percent of people still smoke.

What has been effective is just putting heavy taxes on goods such as cigarettes. Making it very costly to continue to indulge in this habit. We have seen technological innovations on this to try to help get people off nicotine. We have vapes and things like that, where you can kind of wean people off.

AGING with STRENGTH: You noted that the shift toward cheap, nutrient-dense and ultra-processed food began in the 1950s or so. Not coincidentally, in the United States, rates of cardiovascular disease have risen drastically since then. But they haven’t in places like Japan and Korea, so eating like crap is not a necessary result of a prosperous society. So, what about getting the American food industry to not produce such shitty food?

Lo Sasso: You're still looking at this as if consumers are the unwilling recipient, the victim, when I’m arguing that consumers are voting with their dollars. They're scarce dollars, right? They don't have unlimited budgets. And they're voting with their scarce dollars what they want to consume. It's not the food industry doing this to us. We are making choices.

People with limited budgets have to decide how to allocate their funds. Do I want to buy what you would call cheap ultra-processed food, which also happens to be delicious and give me sufficient nutrients to power my body? And I want to spend money on other stuff, too. I want to buy a new iPhone. I want all these other wonderful devices.

AGING with STRENGTH: Again, if we translate your argument to cigarettes and smoking, wouldn't you be saying ‘Don't blame the cigarette companies’? Is there no place where food companies have a responsibility through those “label skirmishes” to be more forthright? The food industry spends an enormous amount of money lobbying Congress to obfuscate the impact of its products.

Lo Sasso: It's a great point. Who really, broadly speaking, quit smoking when this sort of health information was finally made very evident and publicized? It was higher educated, and by and large, higher income people who ended up quitting smoking. Lower income people are still more apt to smoke, even to this day. That does speak to the potential for public health impacts. But so do taxes: simply raising the price of these things. I don't know what a pack of cigarettes costs, like $10-15 now, the cost of producing a cigarette is probably fractions of a cent. We are certainly making it more costly to indulge. If we deem a particular activity to be unhealthy, well, that's the hammer that you have to use.

AGING with STRENGTH: Isn't your argument taking a backwards approach — treating the disease after it develops instead of looking at solutions that prevent the disease from beginning?

Lo Sasso: Waiting for people to develop a problem is clearly sub-optimal. But it’s the only scalable solution that I think we have. The best solution would be prevention. I'm just saying that those forces — prices, the nature of work, the quantity and quality and abundance of food that we have — those factors are just too humongous and civilizational in scope. As a species, we are wired, from a time when food was neither plentiful and work was incredibly laborious and intensive, to consume and store fat for the lean times. You're not gonna scold people into it in a durable, scalable way. You're not going to “label change” people into altering this fundamental aspect of their nature.

AGING with STRENGTH: Doesn't relying on GLP-1s create an equity issue with people who can’t afford to buy them?

Lo Sasso: Yes, just like every innovation in all of human history. Who could afford automobiles? Who could afford horses? As the technology diffuses, as competitors enter, prices go down, we want to facilitate that process, we want to do everything we can to create positive incentives for innovators to develop solutions that help us. I'm ultimately optimistic about all of this. GLP-1s also are kind of just the first generation. There's more coming in the next generation.

AGING with STRENGTH: Instead of that dollar box of ultra-processed pasta, why can’t it be a dollar can of beans? Meaning, what about a little more public education, a little less sugar mandated in sodas. Public health programs, such as those that have required school lunches to offer healthier food, have had real impact.

Lo Sasso: I mean, of course, I guess I could still file that under, you know, tweaking around the edges. I used the box of pasta just as an example to show how cheap a day's worth of calories is and just how extraordinary that fact is. That was not dietary counsel.

“Prosperity Made Us Fat, and Biotech Will Make Us Thin,” by Tony Lo Sasso, Sept. 18, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/opinion/prosperity-made-us-fat-and-biotech-will-make-us-thin-df867234

https://www.anthonylosasso.com/about-me

As this recent Stanford Medicine blog puts it, ultra-processed food “now accounts for nearly 60% of U.S. adults’ calorie consumption. Among American children, that portion is close to 70%. In other words, ultra-processed food is starting to overwhelm the American diet.”

Over the past two decades, the ultra-processed food industry spent more on lobbying ($1.15 billion) than has either the gambling industry ($817 million), Big Tobacco ($755 million) or Big Alcohol ($541 million). Chung H, Cullerton K, Lacy-Nichols J. Mapping the Lobbying Footprint of Harmful Industries: 23 Years of Data From OpenSecrets. Milbank Q. 2024 Mar;102(1):212-232. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12686. Epub 2024 Jan 14. PMID: 38219274; PMCID: PMC10938928.

Oy. Well, full disclosure, I didn't read this in depth--I skimmed your boldfaced questions, it looks like you did a good job holding his feet to the fire.

We are becoming increasingly disembodied as a species thanks to technology--now devolving into technocracy--so if the goal is further disembodiment, then yeah, this is the answer.

However, if you think about food as a key anchor point of human nourishment--not just calories but also culture, tradition, and connection--then hi-tech food makes complete sense as a key to eradicate all of that. What we're left with, then, is a dystopian, Maoist-style situation where corporations and government become our source of sustenance.

No thanks, Bro--I'm heading out to the garden. 🪴

Thanks for posting this interview